The Nullarbor – Anything but Plain

The Nullarbor Plain stretches between Ceduna in South Australia and Norseman in Western Australia, occupying an area of around 200,000 square kilometres. It is bordered by the sea cliffs that fringe the Great Australian Bight to the south and the dusty expanse of the Great Victoria Desert to the north. At its widest point, it spans just shy of 1,200 kilometres.

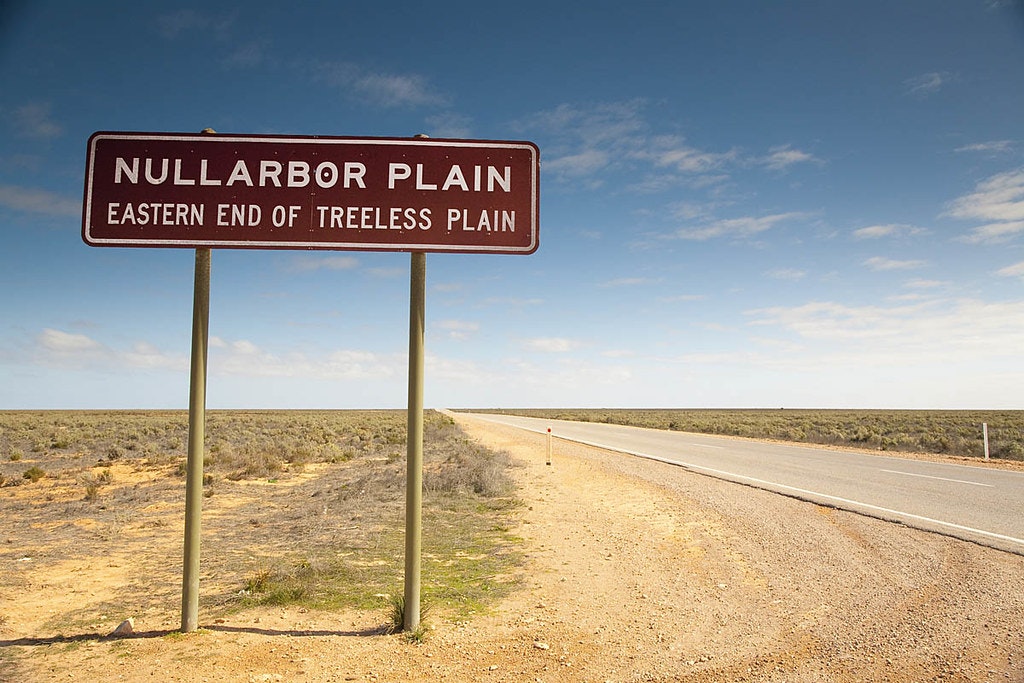

Historically, the Nullarbor was seasonally occupied by Indigenous Mirning and Yinyila people and the area was known as Oondiri, said to mean “waterless”. Its European moniker comes from the Latin “null”, meaning “no” and “arbor”, meaning “tree”. It’s not entirely accurate, but it’s not far off.

This is the world’s largest single exposure of limestone bedrock, so the landscape is far from featureless. Patches of rock push through the earth at regular intervals, in place of trees. It’s actually not devoid of greenery, either. Hardy saltbush and bluebush thrive here and there are a number of flora species, several that are threatened, that can still be found, including the Nullarbor emu bush.

In fact, it’s surprising to realise how much life this arid plain sustains, from birds unique to South Australia, like the Nullarbor quail thrush, plains wanderer, and Naretha blue bonnet, to birds of prey, including the osprey and peregrine falcon, and reptiles like the Nullarbor bearded dragon. Southern hairy nosed wombats survive these climes, as do emus, dingos – although the shy creatures are hard to spot – and kangaroos. Of course, plenty of creepy crawlies hide amongst the saltbush, but the only one that’s considered deadly is the world’s second-most venomous land snake, the eastern brown snake. Just don’t go chasing after one and you’ll be fine. Perhaps the most unusual animal out here, though, is the camel, not a native to Australia. A number of camels were set free after being used to help build the railway and promptly multiplied, with the Nullarbor now boasting up to 100,000 wild, free-roaming dromedaries.

Wildlife abounds, but the same can’t be said for humans in this somewhat inhospitable environment. There are few towns, communities or signs of life, apart from sporadic outback roadhouses and accommodation associated with Highway One, which connects Adelaide and Perth. The handful of inhabited areas of the Nullarbor Plain are found in the series of small settlements located along the railway.

Look on a map, though, and you’ll find a plethora of names noting remote communities once home to railway men, fettlers and anyone else who could scrape together a living out here. Little remains of these settlements beyond their names and a few tumbledown structures. Tarcoola, a former gold mining town is a prime example. Tarcoola is kept breathing by railway relief and maintenance crews, much the same as the almost-ghost-town of Cook, a stopping point for the Indian Pacific. This secluded town has the distinction of sitting on the longest stretch of straight railway in the world. Cook had a recorded population of four in 2009. Alighting from the Indian Pacific onto the dusty stopping point, it’s hard to imagine the population will grow, although it is bolstered by a floating population of train drivers who rest here between shifts.

Back in 1840, it took explorer Edward John Eyre a year to cross this expanse. These days, whether by rail or road, it’s a matter of a few days. And those few days brings a new perspective on the beauty of the Nullarbor. It’s all about almost-empty vistas that stretch for miles and the sheer volume of almost nothing.